Editor’s Introduction

All of us amateur genealogists have encountered the missing 1890 U.S. Census with the note that it was "destroyed by fire." That disaster left a huge gap of 20 years in a census record at a time when our country was burgeoning and many of our ancestors were born, married, or died while others were on the move. In so many ways, that lost census defined our Nation at the critical time when the pioneering America and the westward migration were disappering and stabilizing. This fascinating article shows that "destroyed by fire" is far from the whole story. It appeared in the Spring 1996 issue of  Prologue Magazine and is excerpted here with permission of the U.S. National Archives. In this issue, we read Ms. Blake’s account of the destruction of the 1890 census records. In Part II of her story, to be published next month, we will learn about Civil War veterans records put together during that census.

Prologue Magazine and is excerpted here with permission of the U.S. National Archives. In this issue, we read Ms. Blake’s account of the destruction of the 1890 census records. In Part II of her story, to be published next month, we will learn about Civil War veterans records put together during that census.

Of the decennial population census schedules, perhaps none might have been more critical to studies of immigration, industrialization, westward migration, and characteristics of the general population than the Eleventh Census of the United States, taken in June 1890. United States residents completed millions of detailed questionnaires, yet only a fragment of the general population schedules and an incomplete set of special schedules enumerating Union veterans and widows are available today. Reference sources routinely dismiss the 1890 census records as "destroyed by fire" in 1921. Examination of the records of the Bureau of Census and other federal agencies, however, reveals a far more complex tale. This is a genuine tragedy of records – played out before Congress fully established a National Archives – and eternally anguishing to researchers.

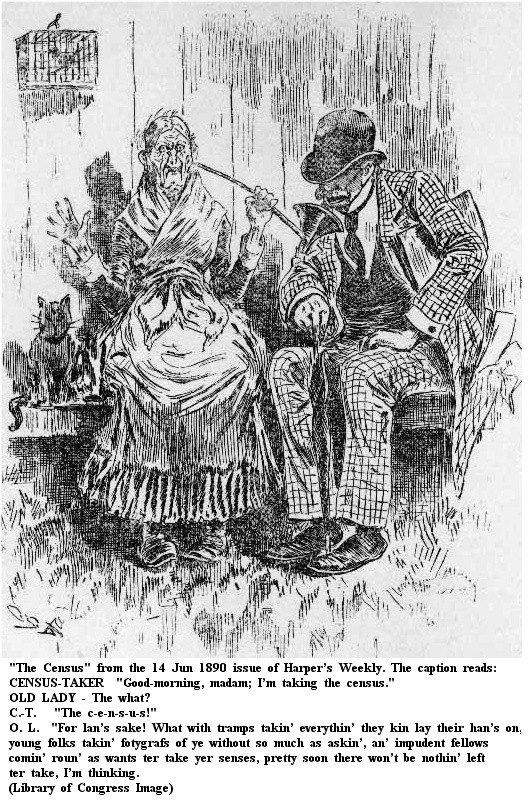

As there was not a permanent Census Bureau until 1902, the Department of the Interior administered the Eleventh Census. Political patronage was “the most common order for appointment” of the nearly 47,000 enumerators; no examination was required. This was the first U.S. census to use Herman Hollerith’s electrical tabulation system, a method by which data representing certain population characteristics were punched into cards and tabulated. The censuses of 1790 through 1880 required all or part of schedules to be filed in county clerks’ offices. Ironically, this was not required in 1890, and the original (and presumably only) copies of the schedules were forwarded to Washington.

June 1, 1890 was the official census date, and all responses were to reflect the status of the household on that date. The 1890 census law allowed enumerators to distribute schedules in advance and later gather them up as was done in England), supposedly giving individuals adequate time to accurately provide information. Evidently this method was very little used. As in other censuses, if an individual was absent, the enumerator was authorized to obtain information from the person living nearest the family.

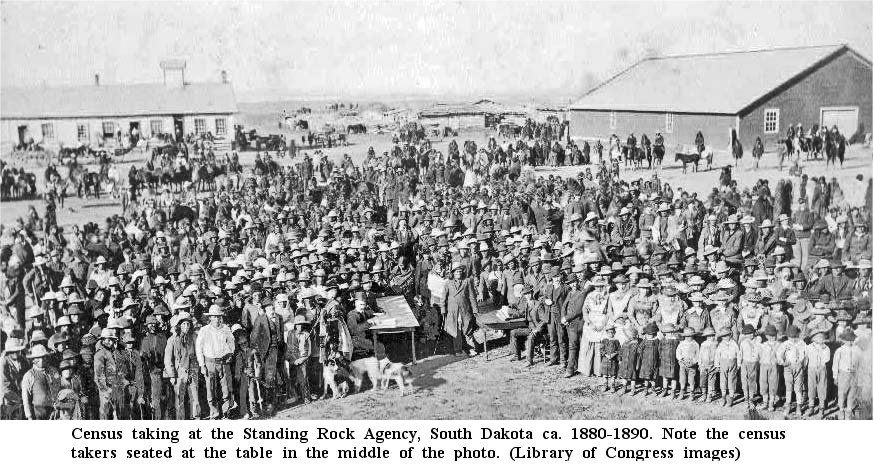

The 1890 census schedules differed from previous ones in several ways. For the first time, enumerators prepared a separate schedule for each family. The schedule contained expanded inquiries relating to race (white, black, mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, Chinese, Japanese, or Indian), home ownership, ability to speak English, immigration, and naturalization. Enumerators asked married women for the number of children born and the number living at the time of the census to determine fecundity. The 1890 schedules also included a question relating to Civil War service.

Enumerators generally completed their counting by July 1 of 1890, and the U.S. population was returned at nearly 63 million (62,979,766). Complaints about accuracy and undercounting poured into the census office, as did demands for recounts. The 1890 census seemed mired in fraud and political intrigue. New York State officials were accused of bolstering census numbers, and the intense business competition between Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, resulted in nineteen indictments against Minneapolis businessmen for allegedly adding more than 1,100 phony names to the census.

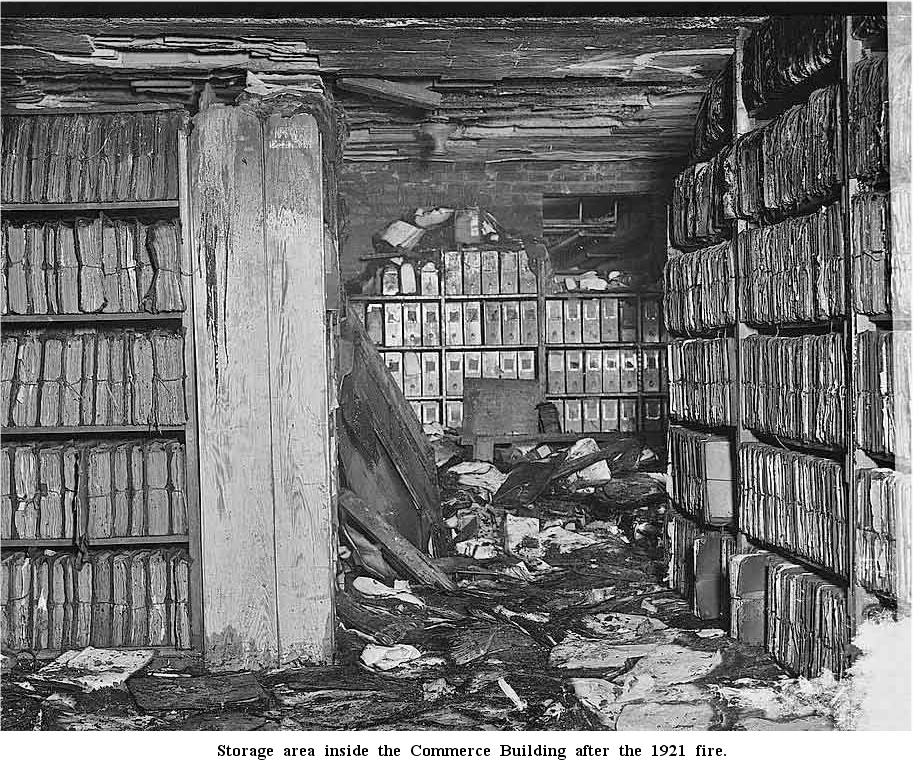

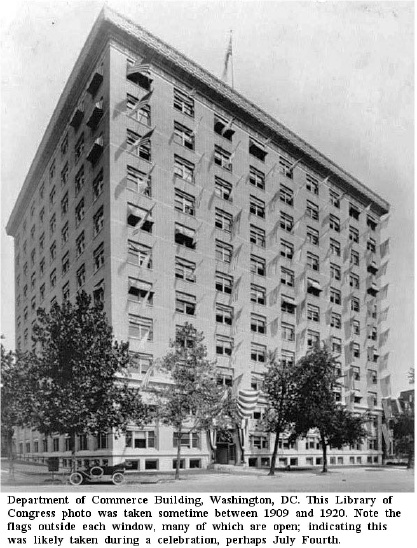

In March 1896, before final publication of all general statistics volumes, the original 1890 special schedules for mortality, crime, pauperism and benevolence, special classes (e.g., deaf, dumb, blind, insane), and portions of the transportation and insurance schedules were badly damaged by fire and destroyed by Department of the Interior order. No damage to the general population schedules was reported at that time. In fact, a 1903 census clerk found them to be in “fairly good condition.” Despite repeated ongoing requests by the secretary of commerce and others for an archives building where all census schedules could be safely stored, by January 10, 1921, the schedules could be found piled in an orderly manner on closely placed pine shelves in an unlocked file room in the basement of the Commerce Building.

At about five o’clock on that afternoon, building fireman James Foster noticed smoke coming through openings around pipes that ran from the boiler room into the file room. Foster saw no fire but immediately reported the smoke to the desk watchman, who called the fire department. Minutes later, on the fifth floor, a watchman noticed smoke in the men’s bathroom, took the elevator to the basement, was forced back by the dense smoke, and went to the watchman’s desk. By then, the fire department had arrived, the house alarm was pulled, and a dozen employees still working on upper floors evacuated.

After some setbacks from the intense smoke, firemen gained access to the basement. While a crowd of ten thousand watched, they poured twenty streams of water into the building and flooded the cellar through holes cut into the concrete floor. The fire did not go above the basement, seemingly thanks to a fireproofed floor. By 9:45 p.m. the fire was extinguished, but firemen poured water into the burned area past 10:30 p.m. Disaster planning and recovery were almost unknown in 1921. With the blaze extinguished, despite the obvious damage and need for immediate salvage efforts, the chief clerk opened windows to let out the smoke, and except for watchmen on patrol, everyone went home.

The morning after was an archivist’s nightmare, with ankle-deep water covering records in many areas. Although the basement vault was considered fireproof and watertight, water seeped through a broken wired-glass panel in the door and under the floor, damaging some earlier and later census schedules on the lower tiers. The 1890 census, however, was stacked outside the vault and was, according to one source, “first in the path of the firemen.” That morning, Census Director Sam Rogers reported the extensive damage to the 1890 schedules, estimating 25% destroyed, with 50% of the remainder damaged by water, smoke, and fire. Salvage of the watersoaked and charred documents might be possible, reported the bureau, but saving even a small part would take a month, and it would take two to three years to copy off and save all the records damaged in the fire. The preliminary assessment of Census Bureau Clerk T. J. Fitzgerald was far more sobering. Fitzgerald told reporters that the priceless 1890 records were "certain to be absolutely ruined. There is no method of restoring the legibility of a water-soaked volume."

Four days later, Sam Rogers complained they had not and would not be permitted any further work on the schedules until the insurance companies completed their examination. Rogers issued a state-by-state report of the number of volumes damaged by water in the basement vault, including volumes from the 1830, 1840, 1880, 1900, and 1910 censuses. The total number of damaged vault volumes numbered 8,919, of which 7,957 were from the 1910 census. Rogers estimated that 10 percent of these vault schedules would have to be “opened and dried, and some of them recopied.” Thankfully, the census schedules of 1790-1820 and 1850-1870 were on the fifth floor of the Commerce Building and reportedly not damaged. The new 1920 census was housed in a temporary building at Sixth and B Streets, SW.

Speculation and rumors about the cause of the blaze ran rampant. Some newspapers claimed, and many suspected, it was caused by a cigarette or a lighted match. Employees were keenly questioned about their smoking habits. Others believed the fire started among shavings in the carpentry shop or was the result of spontaneous combustion. At least one woman from Ohio felt certain the fire was part of a conspiracy to defraud her family of their rightful estate by destroying every vestige of evidence proving heirship. Most seemed to agree that the fire could not have been burning long and had made quick and intense headway; shavings and debris in the carpentry shop, wooden shelving, and the paper records would have made for a fierce blaze. After all, a watchman and engineers had been in the basement as late as 4:35 and not detected any smoke. Others, however, believed the fire had been burning for hours, considering its stubbornness.

Although, once the firemen were finished, it was difficult to tell if one spot in the files had burned longer than any other, the fire’s point of origin was determined to have been in the northeastern portion of the file room (also known as the storage room) under the stock and mail room. Despite every investigative effort, Chief Census Clerk E. M. Libbey reported, no conclusion as to the cause was reached. He pointed to the strict rules against smoking, intactness of electrical wires, and noted that no rats had been found in the building for two months. He further reasoned that spontaneous combustion in bales of waste paper was unlikely, as they were burned on the outside and not totally consumed. In the end, even experts from the Bureau of Standards brought in to investigate the blaze could not determine the cause.

The disaster spurred renewed cries and support for a National Archives. It also gave rise to proposals for better records protection in current storage spaces. Utah’s Senator Reed Smoot, convinced a cigarette caused the fire, prepared a bill disallowing smoking in some government buildings. The Washington Post expressed outrage that the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were in danger even at the moment, being stored at the Department of State in wooden cabinets

Meanwhile, the still soggy, “charred about the edges” original and only copies of the 1890 schedules remained in ruins. At the end of January, the records damaged in the fire were moved for temporary storage. Over the next few months, rumors spread that salvage attempts would not be made and that Census Director Sam Rogers had recommended that Congress authorize destruction of the 1890 census. Prominent historians, attorneys, and genealogical organizations wrote to new Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, the Librarian of Congress, and other government officials in protest. The National Genealogical Society (NGS) and Daughters of the American Revolution formally petitioned Hoover and Congress, and the editor of the NGS Quarterly warned that a nationwide movement would begin among state societies and the press if Congress seriously considered destruction. The content of replies to the groups was invariably the same; denial of any planned destruction and calls for Congress to provide for an archives building.

Herbert Hoover wrote “the actual cost of providing a watchman and extra fire service [to protect records] probably amounts to more, if we take the government as a whole, than it would cost to put up a proper fire-proof archive building.” Still no appropriation for an archives was forthcoming. By May of 1921, the records were still piled in a large warehouse where, complained new census director William Steuart, they could not be consulted and would probably gradually deteriorate. Steuart arranged for their transfer back to the census building, to be bound where possible, but at least put in some order for reference.

The extant record is scanty on storage and possible use of the 1890 schedules between 1922 and 1932 and seemingly silent on what precipitated the following chain of events. In December 1932, in accordance with federal records procedures at the time, the Chief Clerk of the Bureau of Census sent the Librarian of Congress a list of papers no longer necessary for current business and scheduled for destruction. He asked the Librarian to report back to him any documents that should be retained for their historical interest. Item 22 on the list for Bureau of the Census read “Schedules, Population . . . 1890, Original.” The Librarian identified no records as permanent, the list was sent forward, and Congress authorized destruction on February 21, 1933. At least one report states the 1890 census papers were finally destroyed in 1935, and a small scribbled note found in a Census Bureau file states “remaining schedules destroyed by Department of Commerce in 1934 (not approved by the Geographer).”

Further study is necessary to possibly determine what happened to the fervent and vigilant voices that championed these schedules in 1921. How were these records overlooked by Library of Congress staff? Who in the Census Bureau determined the schedules were useless, why, and when? Ironically, just one day before Congress authorized destruction of the 1890 census papers, President Herbert Hoover laid the cornerstone for the National Archives Building.

In 1942 the National Archives accessioned a damaged bundle of surviving Illinois schedules as part of a shipment of records found during a Census Bureau move. At the time, they were believed to be the only surviving fragments. In 1953, however, the Archives accessioned an additional set of fragments. These sets of extant fragments are from Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, and the District of Columbia and have been microfilmed as National Archives Microfilm Publication M407 (3 rolls). A corresponding index is available as National Archives Microfilm Publication M496 (2 rolls). Both microfilm series can be viewed at the National Archives, the regional archives, and several other repositories. Before disregarding this census, researchers should always verify that the schedules they seek did not survive. There are no fewer than 6,160 names indexed on the surviving 1890 population schedules.

More to come ...