I first heard this address "to the Immortal Memory" at the Saint Andrews Society of San Francisco, Bums Night Supper on January 25, 1985. At that time, before the assault of the yuppies the organization was a male group and the dinner was ribald and jolly. Dress was casual, the humor broad, and the fellowship delightful. We came from all walks of life, some recent immigrants from Scotland, carpenters and craftsmen, bankers representing the Royal Bank of Scotland, consular employees, some older immigrants and a lot of us generations from Scotland. The yuppies I refer to came suddenly: lawyers, physicians, brokers, and computer types. Typically, they found out they were of Scottish heritage one day (it was the "in" thing), applied for membership, and granted it, they appeared next meeting in full highland dress. The group now has "formal or highland attire" affairs and the Burns Night is a family affair. I do not go. I miss the old days.

The author, a journalist representing the BBC, Rhoderick Sharpe, was a delightful Scot then living here. I asked for a copy at the time. When I began editing the journal I wrote him in London, where he had been reassigned, for his permission to reprint it. He graciously gave permission, saying that he was amazed than anyone remembered.

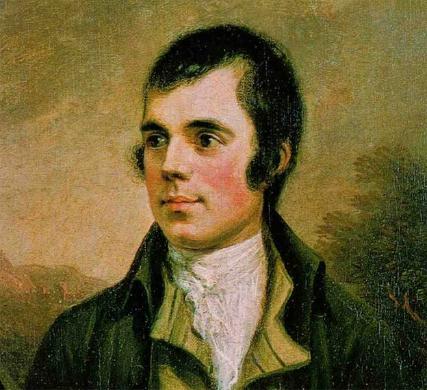

In honor of Robert Burns' birthday, here is the speech

Donald Sanford, CMA Editor

President Childs, Chief Hamilton, Gentlemen:

"Mair nonsense has been uttered in his name

Than in ony's barrin liberty and Christ."

Let's put this quote aside for a minute.

It's a strange thing how every year at this time thousands still gather as we have here tonight to warm up the memory of a man who's been dead these last hundred and eighty nine years. Some of us will cheerfully admit to knowing nothing specifically of Burns but we all know in a general sort of way about him. And then there are those who were raised to memorise a certain Burns poem - usually "To A Mouse" or "To A Mountain Daisy" - for the school recitation competitions of the Burns federation, or having even read books about him, lay claim to that deadly thing - a little knowledge.

In northeast Scotland where Burns' father came from, the farm people in the throes of the agrarian revolution recognised the value of knowledge just as the founders of San Francisco City College who wrote it in foot-high stone letters "ye shall know the truth and the truth will set you free". The motto of the Banff literary society, whose collection of technical books on farming and practical philosophical works of the highest intellectual content circulated through every home in the district, was in Latin, "Otium Sine Literis Mors Est" - Work Without Knowledge is Death.

This salutary knowledge was maybe a sword. Karl Marx would argue that the tremendous upsurge of reading and self-improvement in eighteenth century Scotland paralleled the demise of the peasant farmer, the passing of the land in to the hands of the landlord class the lairds and the emergence of the first working class in Scotland who sold their labour on the land as their children would in the weaving industry and their children's children in the shipyards.

Yet within the same farming communities there was another saying equally current which betrays a superstitious fear of the trouble a little knowledge can let go. "Mony ane's dee'n ill wi vreet" - many a one's done harm harm with knowledge - muttered the old wives and all who thought like them.

My line of nonsense for the night is that Burns was not to be numbered among them. Let's get back to the contentious lines that we left over here.

"Mair nonsense has been uttered in his name

Than in ony's barrin liberty and Christ.

The speaker was a drunk man. I might have known, you say. A drunk man whose words were penned by the only Scots poet whose achievement is being compared by professors and savants of our generation to that of Burns.

Hugh MacDiarmid was a card-carrying communist when he sat down exactly sixty years ago and penned the long, long, long, long diatribe on all things Scottish called "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle".

Absurd you say, what's communism got to do with poetry? It was the man's belief, that's all, but you can't write serious poetry without serious beliefs whatever they are. Burns had his beliefs, too, and a lot of them turned on that high-sounding word, liberty.

MacDiarmid thought the whole business of giving Burns Suppers in fancy places was fairly inappropriate and in his phlegmatic kind of way he said so.

"No wan in fifty kens a wurd Burns wrote," he said,

"But misapplied is a'body's property

And gin there was his like alive the day

They'd be the last a kennin' haund to gie

Croose London Scotties wi their braw shirt fronts

And a their fancy freens rejoicin

That similah gatherings in Timbuctoo

Bagdad - and Hell, nae doot - are voicin'

Burns' sentiments o' universal love

In pidgin English or in wild-fowl Scots

And toastin ane wha's nocht to them but an

Excuse for faitherin Genius wi' their thochts.

MacDiarmid who was a great man but a very feisty one could accuse us of foisting our meaning on to Burns' words. On the other hand, he could be accused of doing the same thing himself. We'll just have to do the best we can but I'll suggest that deep down in us whatever Burns we know or will hear, stirs a right instinct rather than a wrong one.

"Mony ane's deen ill wi vreet" - what were the old women, what are the old women, afraid of?

Here's a poem Burns wrote that didn't make it into the first Kilmarnock edition of his poems. The Address of Beelzebub isn't a bad poem but you have to think about the young man who stakes everything on his first book being a commercial success, as it was. Burns knew enough not to stir things too much with the aristocracy who were, after all, buying the book until he'd made a name for himself.

The circumstances of the poem - the population of the Highlands was expanding at a far greater rate than the Highland,economy. Even potatoes, the great miracle food of the late eighteenth century, couldn't sustain them and the worst winters in 1782 and 1783 had people doing anything to try to get their stock through the winter. Like the woman who kept her cow and its new calf alive on her bed straw or the farmer who took the thatch off his new roof to give to his cattle. No wonder they wanted to emigrate. That was happening to the great great grandparents of people here in this room.

And what got Burns angry was a scheme to prevent people from emigrating. Many of the crofters' landlords belonged to something called the Highland Society and in 1786 they agreed with their leader, the Earl of Breadalbane, to put in money to frustrate five hundred tenants' efforts to get off the estate of McDonald of Glengarry. They'd even bought the ships. But the lairds thought differently and they put up money to improve farming, fishing, and even manufacturing industry there at home.

Burns attack is very subtle - it's a letter purporting to be from Beelzebub, Old Nick, to Breadalbane, commending him and his like for punishing the Highlanders' initiative and even encouraging them to go further.

"Hear my Lord Glengarry hear" he says at one point, "Your hand's owre light on them I fear.

Your factors, grieves, trustees and bailies I canna say but they do gaylies.

Yet while they're only poind and harriet" - mild harassment of Highlanders, nothing more-

"They'll keep their stubborn Highland spirit.

But smash them! crush them a to spails" - little pieces

"And rot the dyvors" - bankrupts, there were plenty of them - "i' the jails'"

We've all heard plenty about people being forced from their lands but here's Burns - this is contemporary history - saying they actually wanted to go. Why? Because over here they saw something they didn't have and that was liberty. Remember this is the chief devil talking so everything he damns is actually praiseworthy in Burns opinion and there's heavy irony here.

"Faith, you and Applecross" - another big landowner - "were right

To keep the Highland hounds in sight!

I doubt na they wad bid nae better

Than let them ance out owre the water" - over here

"Then up amang thae lakes and seas,

They'll mak what rules and laws they please:

Some daring Hancock, or a Franklin,

May set their Highland bluid a-ranklin;

Some Washington again may head them,

Or some Montgomerie fearless lead them;"

Burns knew a lot about the .figures of the American revolution, didn't he? Because like many Scots, and especially Jacobites of his day, he was a profound and admiring sympathiser.

"Till God knows what may be effected

When by such heads and hearts directed

Poor dunghill sons of dirt and mire

May to Patrician" - in other words aristocratic - "rights aspire."

What were Patrician rights? A vote maybe. In the burgh of Ayr, in Burns' day there were 65,000 people of whom exactly 205, all landowners, had the right to vote.

"An where will ye get Howes and Clintons" asks the devil "To bring them to a right repentance?" Sir Henry Clinton succeeded Sir William Howe as British commander in America. And we know what happened, so of course there was no right repentance, but the devil goes harping on about all those things he doesn't want the Highlanders to have.

"To cowe the rebel generation

An save the honor o' the nation?" The British nation, of course.

"They a' be damn'd! what right hae they

To meat or sleep or light o ' day

Far less to riches, pow'r or freedom

But what your lordship likes to gie them?"

So if we're not misreading this, Burns is equating the right to emigrate with the same values as the framers of the First Amendment. As he saw it, emigration was an act of revolution and the emigrants were Scotland's revolutionaries. And he's certainly been read that way in America.

"Burns ought to have passed ten years of his life in America" wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes "for those words of his, 'A man's a man for a' that' show that true American feeling belonged to him as much as if he had been born in sight of the hill before me as I write, Bunker Hill" that is.

The writer of the Old Statistical Account, a sort of eighteenth century reporter, was assailed by complaints from farmers about the attitudes of the farm labourers who wanted everything just so.

"Nice in the choice of their food to squeamishness, it must neither fall short, nor exceed that exact proportion of cookery which their appetites can relish. Care too must be taken that no offence shall be offered them. They must sleep in the morning as long, and go to bed at night as soon as their pleasure dictates. If their behaviour is disagreeable, their masters are at liberty to provide themselves with others, against the first term. And seldom do they fail to give scope for this liberty. When the term arrives, then, like birds of passage, they change their residence or migrate to distant countries."

And where would Burns' sympathies lie? With the farm labourers, you bet.

One last thought about Burns absolute indifference to the lairds' long-sighted and apparently enterprising schemes - which mostly did fail as a matter of fact.

The Scots have a deep suspicion of having one put over on them which persists to the present day. In the very popular 1972 play, "The Cheviot, The Stag and The Black, Black Oil", a radical theatre company called 7:84 paraded their reservations about the way in which they felt Scotland was being exploited again by multinational oil companies and indigenous get-rich-quick schemers like the men who sent the wee Glasgow spiv, Andy McChuckemup, to take a look round.

"The motel - as ah see it - is the thing of the future. That's how we see it, myself and the Board of Directors, and one or two of your local councillors - come on now, these are the best men money can buy. So, picture it if yous will, right there at the top of the glen, beautiful vista, - The Crammem Inn, High Rise Motorcroft - all finished in natural washable plastic granitette. Right next: door, the "Frying Scotsman" all night chipperama - with a wee ethnic bit, Fingal's Caff - serving seaweed suppers in the basket and draught Drambuie. And to cater for your younger set you've got your Grouse-a-Go-Go. I mean, people very soon won't want your bed and breakfasts, they want everything laid on, they'll be wanting their entertainment an that and wes've got the know-how to do it and wes've got the money to do it. So - picture it if yous will - a drive-in clachan on every hill-top where formerly there was hee-haw but scenery."

There was another scheme which Burns opposed and that was a discriminatory tax on whisky distillers which was driving them out of business. Little changes. The Scotch whisky lobby still cries foul when the Chancellor of the Exchequer victimizes whisky in his Budget but they don't have Burns to do it for them.

"Scotland an me's in great affliction" he complained

"Ee'er sin they laid that curst restriction

On aquavitae;"

"Is there that bears the name o Scot

But feels his heart's bluid rising hot

To see his poor auld Mither's pot-

Thus dung in staves" - her still pot's full of holes -

"An plundered o her hindmost groat" - her last cent -

"By gallows knaves" - they should be at the end of a rope he says.

What strange magic is it that links whisky to Scotland. The mythology of Heather Ale, the lost drink that made the last Pict jump over a cliff to his death rather than reveal the secret to invading Norsemen. It inspires good poetry says Burns and without it I'd be finished -

"O Whisky! soul o plays an pranks

Accept a Bardie's gratefu' thanks!

When wanting thee, what tuneless cranks

Are my poor verses!

Thou comes they rattle i' their ranks

At ither's arses!" -They line up nice and smart.

Like every born Scot since the Union of the Parliaments removed the obvious trappings of our individuality as a country, Burns is always worrying about what it means to be a Scot and it is for this I suggest that we venerate and even beatify him at these compulsive annual bashes, however amused he'd be about that.

Scots drink whisky and eat haggis, right? We all know that.

"Mark the rustic haggis fed

The trembling earth resounds his tread

Clap in his wally neive a blade

He'll mak it whissle

And legs an arms and heads will sned

Like taps o thrissle." We're a violent lot, or we rattle a lot of sabres anyway.

"Bring a Scotchman frae his hill

Clap in his cheek a Highland gill" - Scotch whiskey, same effect -

"Say such is royal George's will

An there's the foe" -we suspect Burns of irony here

"He has nae thought but how to kill

Twa at a blow."

This is great, right? Eat haggis, drink whisky, conquer the world? Well haven't we? Some people believe that there is the equivalent of a Scottish diaspora like the lost tribe forever condemned to wander the world but it's patently not true because Scotland's still there.

Scotland to Burns was the place he fretted about in very specific ways - he railed at the Highland Society, he railed at the efforts of the London parliament to regulate the Scotch whisky industry. And at the bottom there was a sense of irony of how did we come to this pass.

To Burns, whisky is the fire of his muse and it's the Scottish spirit and it doesn't always do you favours. 'An Earnest Cry and Prayer' has a very curious last verse full of an agonizing self awareness.

"Scotland my auld respected Mither

Tho whyles ye moistify your leather" - wet your pants

"Till whare ye sit on craps o heather" - heather bushes

"Ye tine your dam" - you piss yourself

What's going on here, a besotted incontinent Scotland? How unlikely.

"Freedom and Whisky gang thegither

Tak aff your dram!" Drink up! Cheers!

Freedom and whisky go together. Scotland is free to do whatever she wants but the reality is that it's sometimes not very dignified and it doesn't matter. "Tak aff your dram! Liberty's the thing."

It's life with no restrictions like Poosie Nansie's doss-house in Mauchline, which Burns visited and came away with a spirited view of the joys of life among the Scottish underclass of beggars, thieves and whores.

"A fig for those by law protected" sings his cast of villains

"Liberty's a glorious feast!

Courts for cowards were erected

Churches built to please the priest!"

Anything goes for Burns. He's not here to moralize about Scotland's position, flat on its back in the middle of a heather bush. As long as it's her choice.

Sir Walter Scott, who was so much more middle class than Burns called him "in truth the child of passion and feeling." And George Gordon, Lord Byron, confided to a friend that someone had lent him "a quantity of Burns's unpublished and never-to-be-published Letters. They are full of oaths and obscene songs" he wrote. "What an antithetical mind! - tenderness, roughness - delicacy, coarseness - sentiment, sensuality - soaring and groveling , dirt and deity - all mixed up in that one compound of inspired clay!"

In a way it's like the New York Times boasting that it contains 'All the News That's Fit to Print'. Burns didn't advertise his poems like that but his work contains a lot more of life than the New York Times contains news.

"Even he an obscure nameless Bard" wrote Burns of himself in that first edition preface, "shrinks aghast at the thought of being branded as an impertinent blockhead obtruding his nonsense on the world."

Well of course he wasn't. His was the most meteoric success of his generation. Maybe you read that Prince is coming to the Cow Palace to play an unprecedented six shows. For Prince to become a superstar was six years of hard work, and his fame is transitory. I think so anyway. Apologies to any Prince fans.

It took Burns in 1786 three months to have the Kilmarnock Edition sell out and six months to be dining with the first lords of Scotland. Was ever fame like this? "Whaur's yer Willie Shakespeare noo?"

What is Burns's Scotland? Here's the muse speaking to Hugh MacDiarmid's drunk man.

Twixt Scots there is nae difference.

They canna learn, sae canna move

But stick for aye to their auld groove

- The only race in History who've

Bidden In the same category

Frae stert to present o' their story

And deem their ignorance their glory.

Burns is asleep but not drunk when his Muse whom he calls Coila comes upon him in a vision. Coila is a sure optimist - and so I think is Burns.

"To give my counsels all in one

Thy tuneful flame still careful fan

Preserve the dignity of Man

With Soul erect

And trust the Universal Plan

Will all protect."

Comforting to know when you're on your back in the heather.

In our generation - I mean really, in the twentieth century it's been the easiest thing to take issue with Burns' conscious optimism by blaming our messes on a national consciousness which venerates him.

In literature there was the second rate and the merely sentimental and Burns seemed to have done the literary spadework on intimate stories of "tough times among the turnips and greens" in what our generation came to deride as the comfy couthy kailyard.

Of course these things are fashions and people are now picking things out of the kailyard which they actually enjoy reading. Then the Scots went to fight for the British Empire - they did indeed fight- for King George and his successors - and suffered terrible losses and came back to find their land gone and they were being dumped on by a distant London parliament. In 1979 the Scots had a chance for a parliament of their own which they turned down making the blind defense that it wasn't enough. "Better a wee bush than nae bield" - a wee bush is better than no shelter at all - is how Burns sealed his letters.

Burns would have appreciated the irony of how the Scots knuckled wryly under to accept the apparently unacceptable, like Russian peasants under the Tsar. But he wasn't responsible for it. Is it any wonder that Edwin Muir, an intelligent and talented poet lost patience and exploded against the cumbersome images of Burns and Scott which he dubbed "sham bards of a sham nation."

He recanted, sort of.

"Burns' gift made him a myth" Muir later wrote. "It predestined him to become the Rabbie of Burns Nights. When we consider Burns we must therefore include the Burns night with him and the Burns cult in all its forms. If we sneer at them we sneer at Burns."

But come on. Burns was a man and not a cheering section, a poet not a politician.

What have I said about his knowledge of love and his empathy with the natural world, about his sense of humour, his devotion to traditional music or his extraordinary grip on Scotch myth that unites us as a people - 0h, but trust the Universal Plan. All will be revealed this evening in the songs and poems we're about to enjoy.

But let's knock Burns off his pedestal and put him back among us at our Burns Suppers where he belongs because he's a great and inspirational companion but thank God he's nobody's saint.

Rhoderick Sharpe, 1985