A haggis is a small animal native to Scotland. Well when I say animal, actually it's a bird with vestigial wings - like the ostrich. Because the habitat of the haggis in exclusively mountainous, and because it is always found on the sides of Scottish mountains, it has evolved a rather strange gait. The poor thing has only three legs, and each leg is a different length - the result of this is that when hunting haggis, you must get them on to a flat plain - then they are very easy to catch - because they can only run round in circles.

After catching your haggis, and dispatching it in time honoured fashion, it is cooked in boiling water for a period of time, then served with tatties and neeps (and before you ask, that's potatoes and turnips).

The haggis is considered a great delicacy in Scotland, and as many of your compatriots will tell you, it tastes great - many visitors from the US have been known to ask for second helpings of haggis!

The noise that haggis make during the mating season gave rise to that other great Scottish invention, the bagpipes.

Many other countries have tried to establish breeding colonies of haggis, but to no avail - it's something about the air and water in Scotland, which once the haggis is removed from that environment, they just pine away.

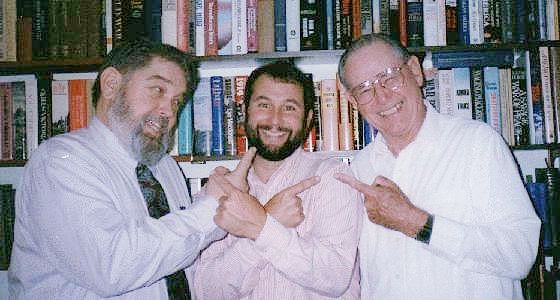

From l. to r., Robert C. McAllister, CMA Webmaster, Frank McAlister,

CMA Database Manager and Robert M. McAllister, CMA Geneaologist Emeritis,

engage in the ancient Scottish rite of "Who's got the haggis?"

A little known fact about the haggis is its aquatic ability - you would think that with three legs of differing lengths, the poor wee beastie wouldn't be very good at swimming, but as some of the Scottish hillsides have rather spectacular lakes on them, over the years, the haggis has learned to swim very well. When in water, it uses its vestigial wings to propel itself forward, and this it can do at a very reasonable speed.

Haggis are by nature very playful creatures, and when swimming, very often swim in a group - a bit like ducks - where the mother will swim ahead, and the youngsters follow in a line abreast. This is a very interesting phenomenon to watch, as it looks something like this :.

__---

/ /

/ /

/-\ /-\ /-\ /-\ / /

The long neck of the mother keeping a watchful eye for predators.

This does however confuse some people, who, not knowing about the haggis, can confuse it with the other great indigenous Scottish inhabitant, the Loch Ness Monster, or Nessie, as she's affectionately known, who looks more like this :

__---

/ /

/ /

/-\ /-\ /-\ /-\ / /

From a distance, I'm sure you'll agree, the tourist can easily mistake a family of haggis out for their daily swim, for Nessie. This of course gives rise to many more false sightings, but is inherently very good for the tourism industry in Scotland.

The largest known recorded haggis (caught in 1893 by a crofter at the base of Ben Lomond), weighed 25 tons.

In the water, haggis have been known to reach speeds of up to 35 knots, and therfore, coupled with their amazing agility in this environment, are extremely difficult to catch, however, if the hunter can predict where the haggis will land, a good tip is to wait in hiding on the shore, because when they come out of the water, they will inevitably run round in circles to dry themselves off.

This process, especially with the larger haggis, gives rise to another phenomenon - circular indentations in the ground, and again, these have been mistaken by tourists as the landing sites of UFOs.

I hope this clears up some of the misconceptions about the Haggis, that rare and very beautiful beastie of the Scottish Highlands (and very tasty too).

I have included here as much factual, scienific material as possible, however more study is clearly needed.

No-one has as yet been able to ascertain the sex of captured Haggis, and partially because of this, scientists assume the haggis is hermophroditic.

This may also be a product of evolution, and does explain the logistic problems of bringing two haggis together - after all, sure footed though the beast is, if two were to mate on a Scottish hillside, it is a long fall down, and a slip at the wrong time may very well result in a reduction by two of the total haggis population.

What is known about Haggis breeding is that, several days prior to giving birth, the Haggis make a droning sound - very much like a beginner playing the bagpipes for the first time - giving rise to the speculation that the bagpipes were indeed invented in Scotland, simply to lure unsuspecting haggis into a trap. At the onset of this noise, all other wildlife for a five mile radius can be seen exiting the area at an extremely high rate of knots (wouldn't you if your neighbour had just started to play the bagpipes?). The second purpose of the noise seems to be to attract other Haggis to the scene, in order to lend help with the birth. This also gives rise to the assumption that Haggis are tone deaf.

Haggis normally give birth to two or more young Haggis, or "wee yins", as they are called in Scotland, and from birth, their eyes are open, and they are immediately able to run around in circles, just like their parent.

The wee yins are fiercely independant, and it is only a matter of weeks before they leave the parent, and go off foraging for food on their own, although it is perhaps a two or three year period before they are themselves mature enough to give birth.

Most Haggis hunters will leave the wee yins, due simply to their size, but when attacked by other predators, they are still able to emit the bagpipe-like sound, which again has the effect of very quickly clearing the surrounding area of all predators, and attracting other Haggis to the scene. This results in a very low infant mortality rate, with most wee yins actually making it to adulthood.

The lifespan of the Haggis is again an unknown quantity, but from taggings done in the Victorian era, we know that some haggis live for well over 100 years.

by John Wilson