Only one man can say he was accidentally bumped from the sky by Charles Lindbergh. It was in 1925 before Lindbergh became Lucky Lindy, first person to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean—back when he was just a goofy flight-school cadet in Texas. Lindbergh's account of the mishap has been published in biographies, aviation magazines, school textbooks and newspapers. Yet the man Lindbergh knocked from the air has never told his story for the record.

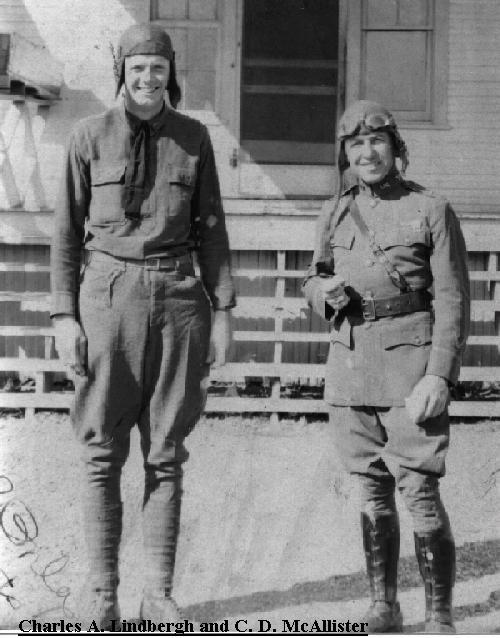

So, meet retired Col. Charles Dawson McAllister. He turned 100 in October, 1995, and he has lived in Orlando FL for nearly 50 years. He is a walking, talking piece of history. He and Lindbergh were the first people—ever—to survive a mid-air plane collision. They were the 12th and 13th people to save their lives with parachutes, becoming official members of the Caterpillar Club, so named because the parachutes were made of silk. He is also a story-teller with an amazing recall. As he sits in his Orlando home—leather shoes shining like a mirror, trousers creased sharp as a blade—he remembers events of past 90 years as though the occurred yesterday.

He was associated with Lindbergh three times over the decades, the first time in flight school. He met Lindbergh again in World War II and in 1954 in Orlando FL. His collision with Lindbergh has its roots in Logansport IN where McAllister grew up and fell in love with flight. "I saw my first plane when I was 14 years old in the summer of 1910," he said. The images of that evening would stay with him to this day.

"The sun was just going down behind a slow rise in the west, a big, red sun sitting on the horizon," he said. The pilot took off, barely getting the plane off the ground.

"He went just over the horizon right into that setting sun," McAllister said, still marveling at the sight. The seeds were sewn. He would become a flier.

First, though, he joined the army during World War I and became a lieutenant. When the war ended, he finished college at Purdue University, graduating in 1920. That summer he moved to Winter Garden, an orange growing center west of Orlando, and worked for a citrus company now known as Roper Growers Cooperative. McAllister's sister had married into the Roper family.

Citrus had no appeal for McAllister. When he had the chance to join the regular army as a career officer, he did. He became a lieutenant in a field artillery unit in Washington. In February, 1924, the seeds of that 1910 Indiana night germinated, and McAllister was accepted into Army flying school at Brooks Field in Texas. So was Lindbergh.

"Actually, he came down to Brooks Field in an old ram-shackled plane, put together with bailing wire," McAllister said. The plane was so decrepit a corporal ordered it off the field, historical records show.

McAllister and Lindbergh were in the first class to receive parachutes. They needed them.

On March 26, 1925, McAllister, 29 and Lindbergh, 22, were paired for a three-plane training run. Their instructor was the enemy. Lindbergh was the left-wing and McAllister the right, both behind a leader.

Lindbergh wrote in his account that after the leader pulled up, he kept diving at the target. When he pulled up, he hit the bottom of McAllister's plane. Lindbergh saw McAllister get ready to jump and then bailed out himself. McAllister remembers the crash a bit differently. He said he planned to watch Lindbergh, who had the habit of ignoring the instructor and doing as he pleased. "But I took my eyes off Lindbergh," he said, and when he looked back, Lindbergh was underneath. "I yanked back and tried to avoid him. The planes locked together, so we just jumped out." They floated earthward and into the record-books, and the two men met on the ground.

What did Lindbergh say? "He didn't say anything. I did all the talking," McAllister said. Within an hour, both were back in the air. Nine days later they graduated from flight school.

The next time the two met, Lindbergh was the world-famous flier who had crossed the Atlantic in May 1927 and the grieving father whose son had been kidnapped and killed in 1932.

World War II had begun. Henry Ford had asked Lindbergh to help design a factory for building B-24 bombers in Detroit. Lindbergh went cross-country to learn about the bomber, and on April 16, 1942, he ended up in Albuquerque, NM, to see McAllister, who ran the nation's only B-24 training program.

"He had matured a lot," McAllister said. But he remembers Lindbergh as having little time for pleasantries.

"He was a non-drinker, was a very naive sort of fellow. There were a lot of things he wasn't interested in and didn't want to learn," McAllister said. They met in a hotel, did not mention their collision, and talked about the bombers.

Lindbergh had fonder memories of their meeting. In The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh, published in 1970 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, he wrote: "Breakfast with Colonel [C.D.] McAllister at 7:30, (I received a note of invitation from him when I arrived at the hotel last night.) McAllister and I collided our SE-5s while we were attacking an observation plane during maneuvers at Kelley Field in 1925. We both had to jump but landed without injury. McAllister, who was a student officer at the time was a bit stuffy about it and claimed I ran into him. I didn't think so, and thought he was out of place in the three ship formation we were flying. However it hadn't occurred to me to question who was at fault. We had been doing a dangerous type of flying, and our C.O. and instructors took it as a matter of course."

"Since I was a cadet in 1925 and McAllister an officer, I had no opportunity of getting to know him well. But this morning I found him to be an interesting and pleasant friend. If he ever held any resentment toward me, as I was told was the case, there was certainly no trace of it remaining. And all during the day he went out of his way to be as considerate and helpful as possible."

The last time the men met was in April, 1954, when Lindbergh visited Orlando to scout for a potential site near Wekiva Springs for the US Air Force Academy. Because McAllister knew Lindbergh, officials prevailed on the then-retired colonel to accompany Lindbergh around the city. A photograph of the two was published in the Orlando Sentinel. "Every state in the union, I guess, wanted the Air Force Academy," McAllister said. But despite his efforts, the academy was awarded to Colorado, where it is today.

McAllister flew 6,200 hours for the Army before he retired, and he flew 5,000 hours in his own planes. His best flying memory was in 1960 when he was 64 and flew 19,000 miles to the southern tip of South America. The trip took three weeks. "I think in some respects it was the premiere flying of my career," he said.

He has one wish as he approaches the century mark. He is a member of the Order of Daedalians, a society of pilots of heavier-than-air craft—no blimps or balloons. The title founder-member is reserved for men who won their wings and military commissions before the World War I armistice on November 11, 1918. McAllister would like to find an unknowing pilot who is eligible.

While he waits to find one, McAllister will tell his stories and play his two rounds of golf a week. It's ironic, but his favorite plane of the 130 that he has piloted is the very model he was flying when Lindbergh collided with him in 1925, as SE-5.

Like McAllister, they aren't making them that way any more.

[From the Orange County Register, 22 February 1995, courtesy of Jean McAllister Elrod, daughter of retired Col. Charles Dawson McAllister. Reprinted in the June 1996 quarterly journal of the Clan McAlister of America.]